The Pangea Code is a new type of alphanumeric code. It is represented by rational numeric characters based on digital numbers, but using only four bars instead of seven, along with a new alphabet composed of 16 characters—4 vowels and 12 consonants—represented in sinusoidal form. This system is intended as the foundation for a project aimed at developing a new international language, “IBL” (International Basic Language). Throughout human history, writing has always been the engine of cultural and scientific growth for civilizations across the globe. Yet, at the dawn of the third millennium, we are witnessing a stagnation in the development of political, economic, and social models. One reason might be the absence of a truly universal language, capable of uniting humanity in the effort to positively advance global civil society. Language is fundamental for achieving basic objectives that allow peoples to exercise self-determination, ensure cultural and scientific progress, foster economic development, and guarantee equal rights and individual freedoms. Consider, for instance, the incredible scientific advances enabled by the introduction of zero and the metric system—without which we might never have reached the Moon. The Pangea Code could serve as the right tool to achieve these goals, supporting the creation of a new language under the guidance of UNESCO and all UN member countries—a language that synthesizes the linguistic characteristics of all ethnicities on Earth.

The mere thought of such an ambitious project will attract sharp criticism, especially from scholars of classical languages, who may object to a universal mass culture. Yet, this language would embody the best elements of each individual culture and civilization, extracting the valuable aspects of every classical or modern language. Other criticisms may come from those who argue that an international auxiliary language already exists—English—but even English is limited, with numerous irregularities, and few speakers truly consider it their own. By contrast, “IBL” would be inherently universal, created with contributions from all willing participants, subject to review by an international and intercultural steering committee.

Since ancient Greece, the development of language has significantly advanced mathematical and philosophical sciences. During Roman times, Latin established the foundational rules of law, enabling the Romans to dominate the Mediterranean and beyond. The fall of the Roman Empire and the fragmentation of written legal culture led to the Dark Ages, with knowledge preserved mainly through monastic orders. The Renaissance revived classical culture, revitalizing Neo-Latin and Anglo-Germanic languages, laying the groundwork for the concept of a nation: a people settled in a defined territory with a shared language and culture.

The Enlightenment saw European languages flourish, greatly advancing engineering, economics, medicine, law, and political philosophy. Combined with early liberal reforms, this enabled the establishment of democratic principles, most notably the separation of powers, which underpinned political revolutions that continue to form the constitutional foundations of modern Western democracies.

Humanity today finds itself in a unique historical position, with tremendous scientific development in medicine, engineering, and communication, alongside severe challenges such as pollution and nuclear weapons. The 20th century will be remembered for major scientific discoveries and the centrality of petroleum in the global economy, fostering both progress and environmental harm.

A universal language of peace could help prevent the 21st century from being remembered as the century of nuclear catastrophe, reducing the risk of wars fought with modern nuclear weapons or attacks on civilian nuclear facilities, as evidenced by Chernobyl and Fukushima. Ideally, a single global language would foster peace, democracy, and mutual understanding across economic, political, and religious spheres, creating bridges instead of walls. The ultimate goal would be a peace where every person can say, “I have no enemy,” rather than merely the absence of war among cultures and religions—a true social advancement.

Of course, there is a potential downside: if the new international language were misused to propagate authoritarian political systems, the risks would be significant. However, recent digital democracy tools could ensure effective governance, limiting potential abuses while enabling direct democratic participation.

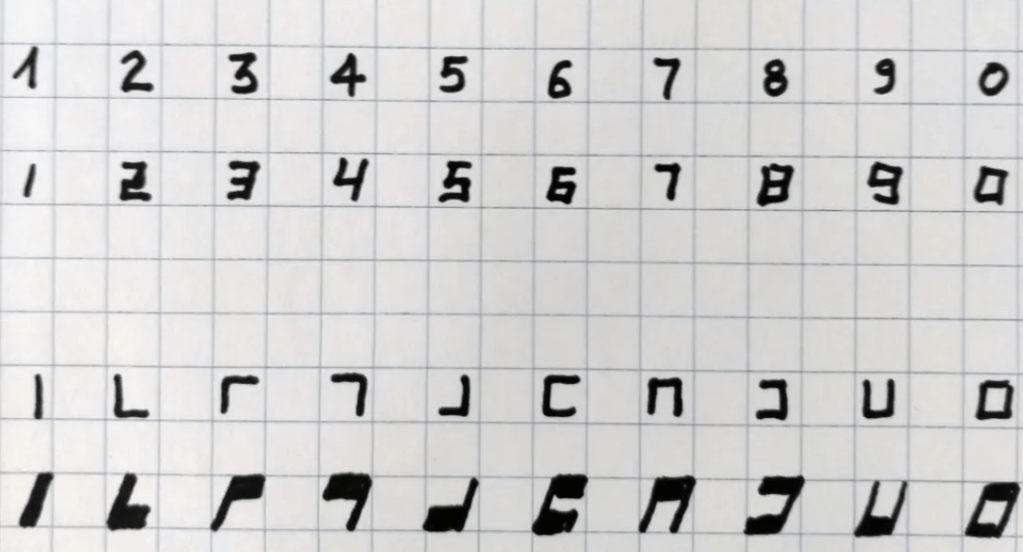

The Pangea Code itself is an extremely rational and visually coherent alphanumeric system. Its numbers, derived from the digital numbers of the 1970s, require only four bars instead of the seven used in classical Arabic-inspired numerals. Numbers are logically constructed using the sides of a square: zero represents all sides, one only the right vertical side, numbers two to five use two sides (with two resembling an “L” rotated clockwise for the others), and six to nine use three sides (six resembling a “C,” rotated clockwise for the rest).

This numeric rationality aligns perfectly with its intended use. Adoption would require no functional change from today’s decimal system (“S.I.”), but the characters would be easier to write than Indo-Arabic numerals. The main challenge is convincing the international community to adopt them, particularly the few remaining countries that resist the metric system.

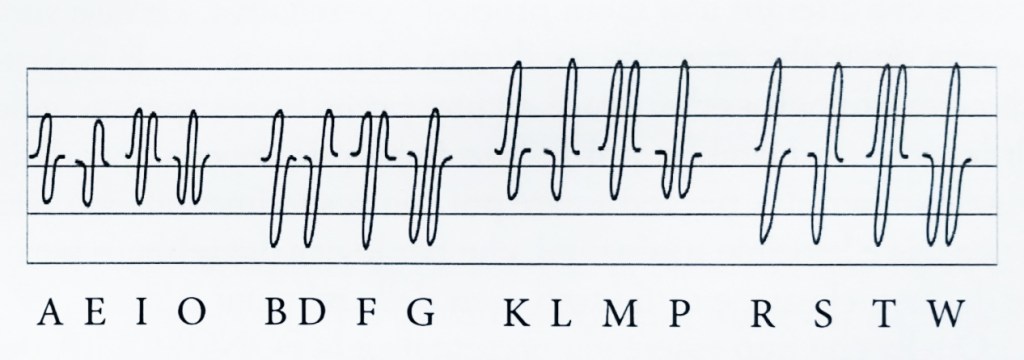

The alphabetic characters present a more complex challenge. The Pangea alphabet—16 characters, 4 vowels and 12 consonants—is designed to avoid common confusions (e.g., “O” vs. “0,” uppercase “I” vs. lowercase “l”), using sinusoidal lines across two horizontal and vertical levels for clarity.

Creating a new language from scratch is a massive undertaking, requiring international cultural oversight—ideally UNESCO—and commissions of representatives from all UN member countries. An international steering committee of 3–4 experts would define rules regarding media communication, international impact, and grammar. The process would begin with a survey of all existing languages, extracting positive features and avoiding negative ones, followed by leveraging the Pangea Code for maximum potential.

The next phases include harmonizing phonology, constructing a preliminary lexicon, defining syntactic rules, and producing initial translations from classical and sacred texts. Phonology should be concise: vowels should have single, unambiguous sounds (e.g., a simplified Italian-style system) and consonants should be short and straightforward. The vowel “U” would be removed, symbolizing linguistic evolution beyond primate-like speech.

This project addresses the global language barrier, which limits access to cultural and democratic participation, especially for those with fewer learning opportunities. A universal, rational, and easy-to-learn language would lower educational costs, accelerate language acquisition, and provide a basic culture to citizens of poorer countries. Early adoption would also stimulate economic activity via translation and implementation.

Ultimately, the goal of an International Basic Language based on the Pangea Code is not a perfect language, but a language of peace and harmony between humanity and nature, facilitating understanding, democratic participation, and a sense of friendship among speakers worldwide.